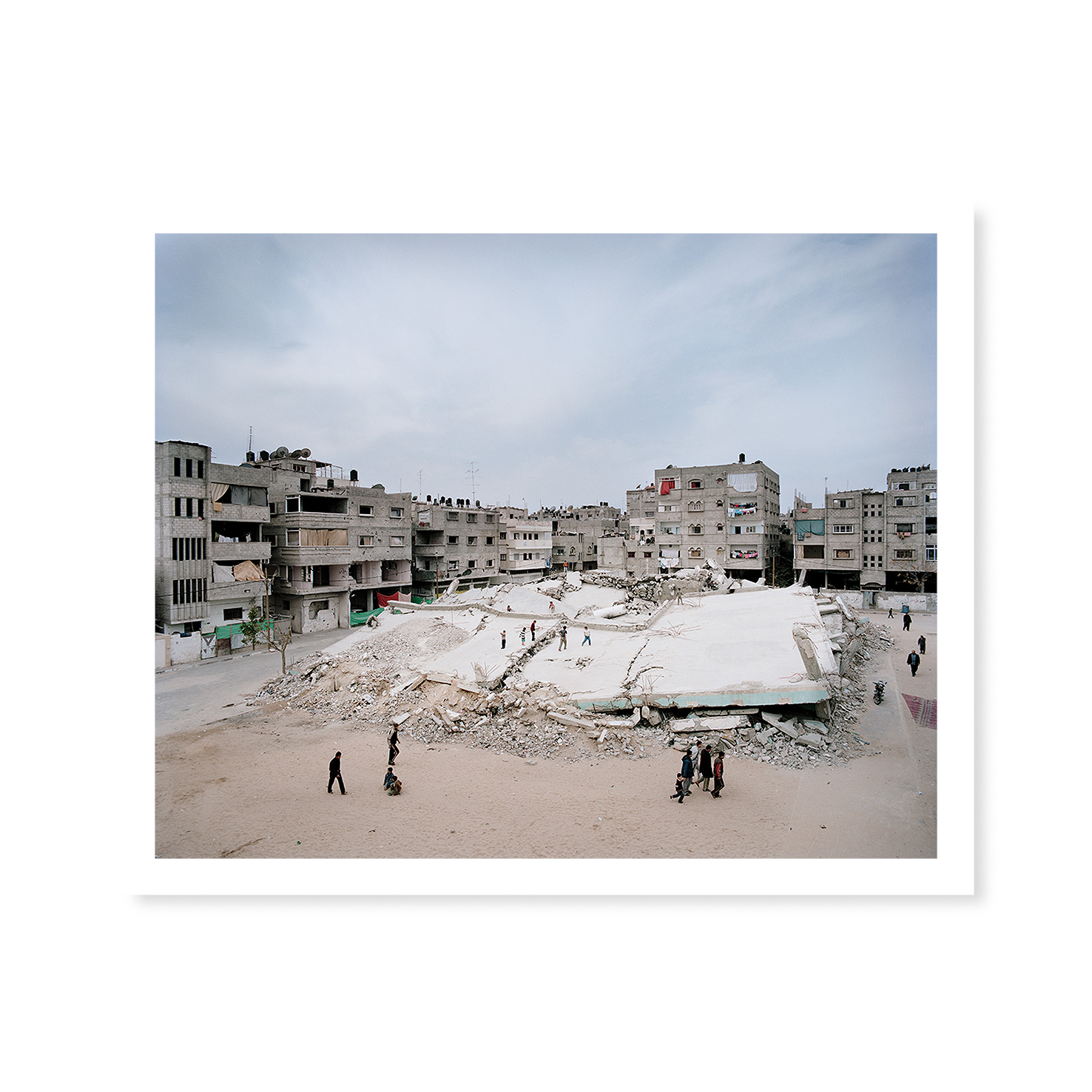

“I’m interested in the subsequent change, how you can read from the wounds that war inflicts on a city the changes for living together.”

The photographer Heinrich Völkel, born in Moscow in 1974, has repeatedly taken photographs in war-torn cities. The quality of human beings to adapt to adverse circumstances is a phenomenon he depicted in many places.

It is said that your photography is characterized by improvisation. What do you mean by that?

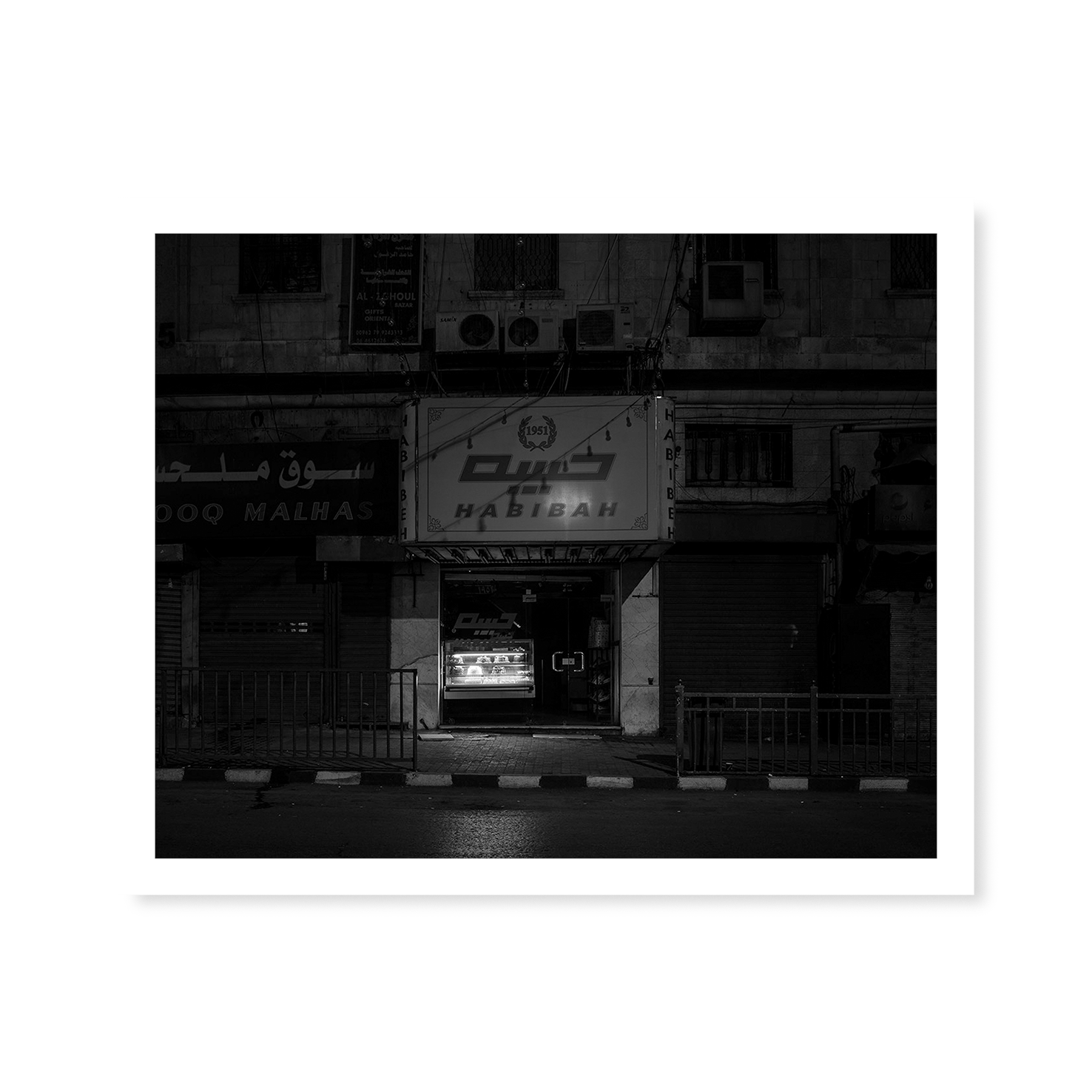

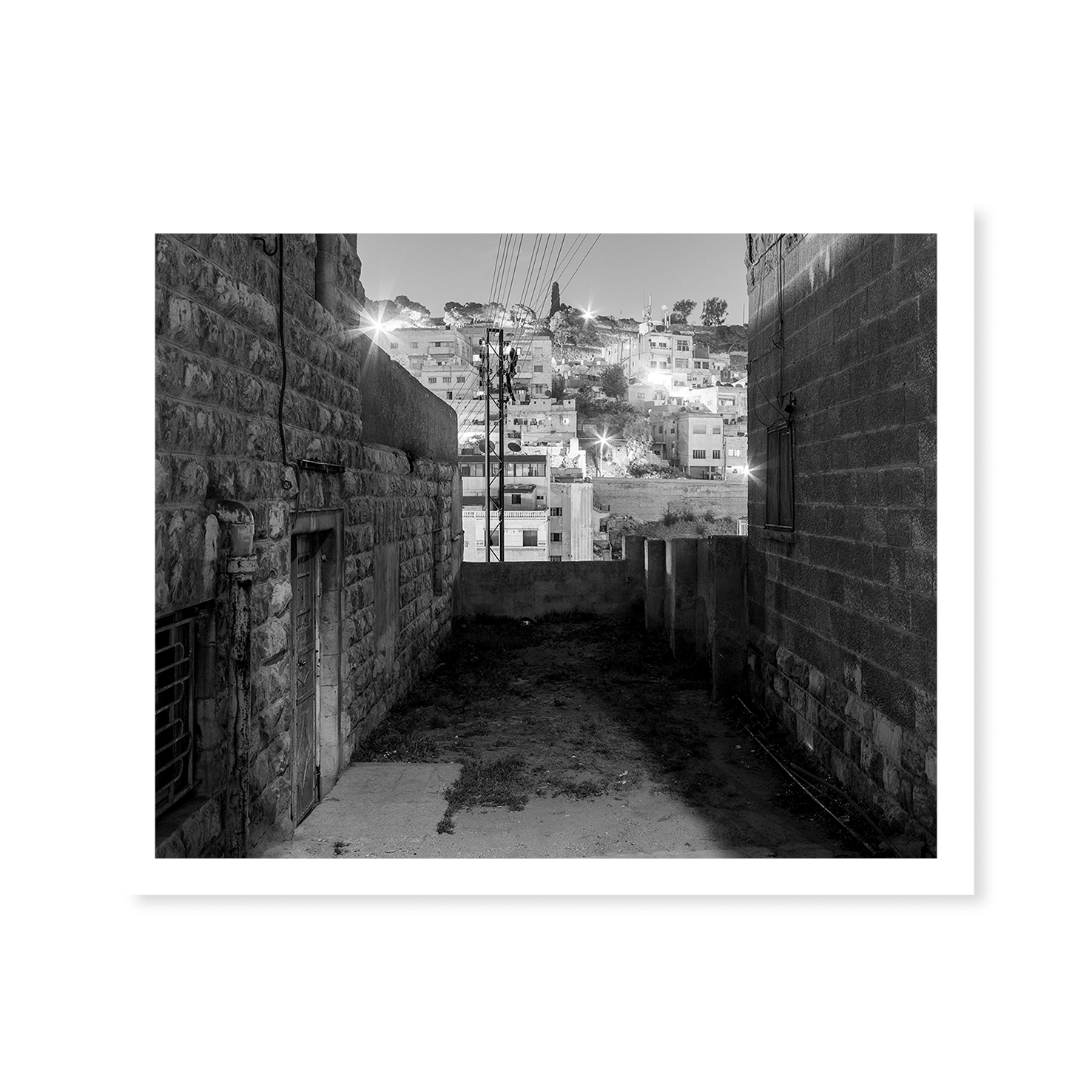

Basically, that means that I deal with what I find. I come from a photojournalism background and have now more or less switched to a documentary subject. I deal with reality or the image of reality, which means that you have to adjust to things that happen. Let’s put it this way, I never take pictures in a street-like way, never of things that I simply find, but I only take pictures when I have an idea that I can follow. Then there are images that exist relatively precisely in my head beforehand, which I then search for or work on until I find them. But quite often it also means simply reacting and recording things, for example from the Gaza series there is this one picture with the fan on the ceiling, which also came about by chance. I photographed a destroyed mosque in the street before, then the neighbours asked me into their flat to show me the burnt out children’s room and there I discovered this motif on the ceiling. The way I often work is that I have a shoot list of ideas and locations that are important to me that I work off of. With the series from Amman, it is precisely this interweaving of old and new between the old city and the new Amman, between the future and the past, that was important to me. That’s the kind of thing I look for and then develop a relatively concrete idea.

How tightly is the planned and how is the improvisational part?

That’s pretty fluent, I think. I always have a concept, sometimes formulated, sometimes it exists only in my head. And then I work my way along that theme. But if I drive by something and think, hey that’s great, that fits in, I’ll still get the camera out. Over the years, a kind of process has established itself with me. I have certain cornerstones that I then work off of because they are quasi captivating in terms of research or subject matter. But these are often pictures that are later thrown out because they are too well thought out. In the end, I always try to be open to moments, then sometimes I turn around and take the picture.

In your reportages not only people play a role, but also geography and architecture in particular. Is that because you studied architecture for a short time?

I come from a family of civil engineers and it was my parents’ wish that I should become an architect. That’s why I studied architecture, but fortunately I had already passed the entrance exam for the Lette-Verein in Berlin. Basically, I’m interested in the city or the architecture. People always say that architecture is the fourth art, so to speak, which combines certain parameters of necessity and creativity in one process, and that’s what connects it to photography. Photography, after all, can become art, even though it was born out of necessity. This already overlaps strongly with the image of how architecture is created. I’m also very interested thematically in the city, which I see as an organism. The layering of history in particular places, what such built environments can tell us about how we have lived. I see it as a bit archaeological.

You also portray people or society through architecture, so to speak. Architecture as a mirror of society.

Photography is the medium of our time, which records how we live and shows the next generations how our world used to look like, how cities used to look like. And the same function has, for example, a temple in Greece that tells us today how people lived in those days. Just like the murals in Pompeii. I have nothing against people, of course, I like to photograph them, but in the process of moving away from a very journalistic approach to a documentary artistic one, I decided for myself that I would use architecture as a mirror for people’s lives.

You don’t shy away from adverse circumstances or social hotspots, are those your favorite projects?

Yes, I think that the extremes can reveal a lot about human coexistence. Whether it’s Grozny, Cyprus, or Gaza. I never go there when it’s banging and smoking, but usually shortly after. I’m interested in the subsequent change, how to read from the wounds that war inflicts on a city the changes for living together. I’m not an adrenaline junkie and I wouldn’t call myself a war photographer or a crisis photographer, but I’m just interested in how society endures such extremes.

You once said I always hold my camera straight because I like it that way. What’s that all about?

Yeah, that’s probably the bane of architectural photography already. I kind of have a tendency to keep my camera straight to avoid plunging lines. Maybe that’s also because after the fall of the Wall, as a non-trained photographer, I photographed cover pages for an architecture magazine with a rented view camera from PSL in Leipzig. 1993-94. you always had to straighten the view camera to avoid plunging lines. Somehow it got stuck with me. It really hurts me when lines fall. I also have this tendency to always use the same focal lengths, 35 or 50mm, this way of seeing has somehow become established with me. A very straight look. I don’t need that dynamization in my personal work and I try to take that out as much as possible.

With a job, I’m sometimes forced to leave that path, but with my stuff, I’d rather forgo the pictures if I can’t do it my way.

Who are your clients, do they approach you or do you make suggestions? What distinguishes the free series of pictures from the commissioned works? Do you take the same approach to an assignment as you do to freelance work?

Mentally, yes. It has a lot to do with preparation, with thinking about what you want and what you are doing. Now I don’t do that many jobs at the moment. For the last 1,5 years, after 20 years of photography, I have consciously taken some time off to take care of my photography again. I always felt that when you work a lot, your own comes up short. With my projects, it’s always the case that there’s a trigger. While showering or drinking coffee, on the internet, seeing something, hearing another picture, a news item, reading something on page 3 under miscellaneous, everything can be the trigger. In the past, such an initial spark was often the reason to propose something to the customer, the Stern, die Zeit, whoever. I’ve tried to succeed in the 60/40 ratio before with stories I’ve suggested myself, and it’s worked often enough. And it’s the same with my own work. There is an initial spark and that forces me to deal with the topic. For example, Ostkreuz is now planning a new exhibition on the theme of Europe in the autumn, which is due to open on 1 October. Then I find a topic that fits in there, based on some initial spark in my head like that.

You also exhibit a lot, now also soon with Ostkreuz, like for example in CO Berlin, Münchner Stadtmuseum, you also had exhibitions. What meanings do exhibitions have for you? What opportunities do they offer?

When I do a freelance project, I often shoot with an exhibition in mind. I try to imagine how the picture would look on the wall while I’m producing it. I’m not one of those artists who says I don’t care, I’m just doing this for myself – yes I am – but of course I think about my audience, what have they already seen of the world, or how can I tell a story so that it is new and also enduring. If we come back to Gaza now, this decision to transport the content through architecture instead of doing classic crisis area photography and photographing crying children with googly eyes. You have to find a form that will last. While I’m photographing, I think about it – should it become a blog, an exhibition, etc., that already plays an important role. The exhibition is actually for me always the place where I can show a work.

What will be the next exhibition / project?

That’s now October 1. The exhibition opening will take place at the Akademie der Künste on Pariser Platz in Berlin and is entitled “Kontinent auf der Suche nach Europa”. A joint production of Ostkreuz photographers, on which we have, I think, 5, or 4 years from the first idea, until the exhibition opening brooded and produced. Originally I wanted to photograph something else, started to do so, but then, due to current political events, thematized the closed borders during the Corona crisis.

Only Ostkreuz photographers?

Exactly. We do this every 4-5 years. Ostkreuz always has an exhibition that has a theme. We always sit together and think about what we’re going to do next. Even before a theme has been decided on, some already start taking pictures and since we always have a monthly jour fixe, where we meet once a month in the evening and show each other pictures, the desire to do something and develop a theme always grows in the others. During Corona we did this online and weekly. This is a continuous process, that one is always dealing with some subliminal topic. All of them. And we’re trying to bundle that as best we can. Fortunately, thanks to our good reputation, we then always find someone who wants to exhibit the results. Whether this is the “Die Stadt: Of Rise and Demise” in the CO, or “Über Grenzen”, in the Haus der Kultur in der Welt. Then our 25th anniversary Best of exhibition, so 25 years of Ostkreuz, which was shown in Paris by the Goethe Institute. That also has something to do with the fact that it is of course interesting that 21 really different photographers are trying to interpret a theme. There is of course a cornucopia of ideas and different designs that can be very exciting for the viewer. After all, there is already a signature, an attitude of mind, or a basic framework of what interests you in photography or in the world, which forms the basis of the Ostkreuz Kollektiv, and to see these 21 positions on the wall within this framework is always quite varied and interesting, which is why I think it works well.

Why did you go to Ostkreuz? How did that happen?

I was asked in 2004 by Jordis Antonia Schlösser, who is still a colleague at Ostkreuz. I photographed a lot for Stern and SZ magazine back then. We met once somewhere and she asked me if I was interested and then I introduced myself to Ostkreuz and they took me on. Well, I have to say, of course, they were already my heroes. While I was studying photography in Berlin, or shortly before, the Nicolaische Bookshop published their first book. I had to have that. I once lived in Steglitz for half a year and every day on my way to school I had to pass a bookshop where the book was on display. This book has already been a treasure for me, this has inspired me a lot. I also come from the East, from the GDR, so to speak, and knew Ute and Werner, Sybille Bergemann, Harald Hauswald and Maurice Weiss. Their reputation preceded them and they were firmly booked in my imagination of what good photography is. So of course I felt honored that they asked me. I was with laif before. But Peter Bitzer didn’t hold it against me that I switched to Ostkreuz. I still have a very good relationship with Peter Bitzer and try to maintain it.

More recently you have devoted most of your time to teaching photography, i.e. readings, workshops. You have a lectureship, too, I believe?

No professorship, I’m a teaching assistant. I do both, practical and theoretical mediation. At some point the Goethe Institute asked me if I would like to do a workshop. Through my work in Russia and the Middle East, the series in Amman and Iran, various teaching assignments, I have noticed how much knowledge has accumulated, very practical knowledge. Also how to deal with creative hangups, etc. I thought this would actually be a good time to pass that along. I just enjoy helping others along the way. If there is one teaching principle that underlies my understanding, it is Strengthen, Strengthen. I’m not one to say that’s crap, not like my teacher at the Lette Verein who has torn up a baryte print you spent hours tweaking. That is for me still a deterrent example of how not to proceed, but I am always interested in finding out what the other person can do well, what is his vision, what he sees and sometimes also to tell someone honestly when he sees nothing at all. You might have to learn to deal with that, too. But I’m all about finding out and filtering out where each other’s strengths are and encouraging that instead of saying that’s crap. My perception is also only a certain perception, I am subject to certain traditional images, let’s say how I grew up in photography. For example, I thought it was totally crazy when I was in Iran and I had a suitcase with about 20kg of photo books in it and everyone picked up the photo books and looked at them from behind. Because they read the other way in the Arab world. And that was not at all clear to me before, that suddenly this whole didactic that you build up when you construct a series, for example in a photo book, is completely shaped by the cultural context in which one grew up. So, that was a moment for me where I started to question what one actually does and how? Someone understands this now and so and so because he or she comes from the context and therefore has a completely different view of things. For one person, for example, yellow watering cans are totally interesting because they don’t exist in his culture. On Greenland, for example, relatively few people ride around on bicycles and we find that strange, while the Icelanders might find it particularly interesting when they visit us. And we are amazed that they have seal for breakfast. Seal cereal. To perceive these cultural differences is just incredibly important to me. I just did a cooperation project with an artist from Jordan, now in Corona time, because it’s always important to me to get these influences and not just in our little filter bubble here in Germany. How do claims become relative and what can photography achieve. Does the photography I do work in a different cultural context. That’s the reason why I like to teach, because I get so much back and because long lasting friendships are formed, which are totally valuable for me. It still makes me happy when you come back to Amman 5 years later and meet someone who has found his way in photography, and you know that you have contributed a little bit to it, so that inspires me.

What advice would you give to someone starting out?

Do, do, do!!! And, I see this now in my students and also consider it very important that you get out of this filter bubble in which you move yourself. It’s not so much about whether it’s on the internet or photo books or bicycles without gears or vegan food or stroking animals, it’s about being as open as possible to the world and keeping your eyes open. Also to see beyond the exotic what is going on out there and to develop a keen nose for what is interesting and exciting and what the world is all about. Anyway, that would be what I always try to pass along.