“i sometimes stand next to the same intersection for hours and am completely exposed.

It’s dusty, the noise is distracting, and at such moments I ask myself why I can’t just shoot digitally or at least on film.”

Niklas, you grew up on Lake Constance and worked there for a long time. What brought you to your new home in Frankfurt and when did you discover photography for yourself?

My parents subscribed to National Geographic and Geo magazines. For me as a little boy, the photo reports in it told exciting picture stories about mysterious worlds and things unknown to me, in addition to the Asterix booklets.

My father documented our family life with the camera for a long time, partly developed and enlarged the pictures himself.

Slide nights were always great fun for us, not least because we only had a rickety black-and-white TV that usually didn’t work anyway (it stayed that way until the 1988 Olympics).

At some point, of course, I wanted to take pictures myself.

When I was 11, I had my first darkroom in the laundry room. From then on, photography never let me go. Although I studied law and worked as a lawyer for a few years, I photographed more than ever before to compensate for this. So it was almost inevitable that one day I hung up the law to deal only with photography. Despite some dry spells that followed, it was a decision I have not regretted.

I came to Frankfurt because I was helping to develop3D photogrammetry scanners for a company in Friedrichshafen at the time and we were setting up a3D scanning studio in Frankfurt. I was immediately impressed by the liveliness of the city. When I met my wife one beautiful summer evening on the Main, I was hooked. In the meantime, we live here with our two children as convinced elected Frankfurters.

Near the main train station I found a studio space with a darkroom and – abandoned by all good spirits – plunged into the crazy adventure of wet plate photography.

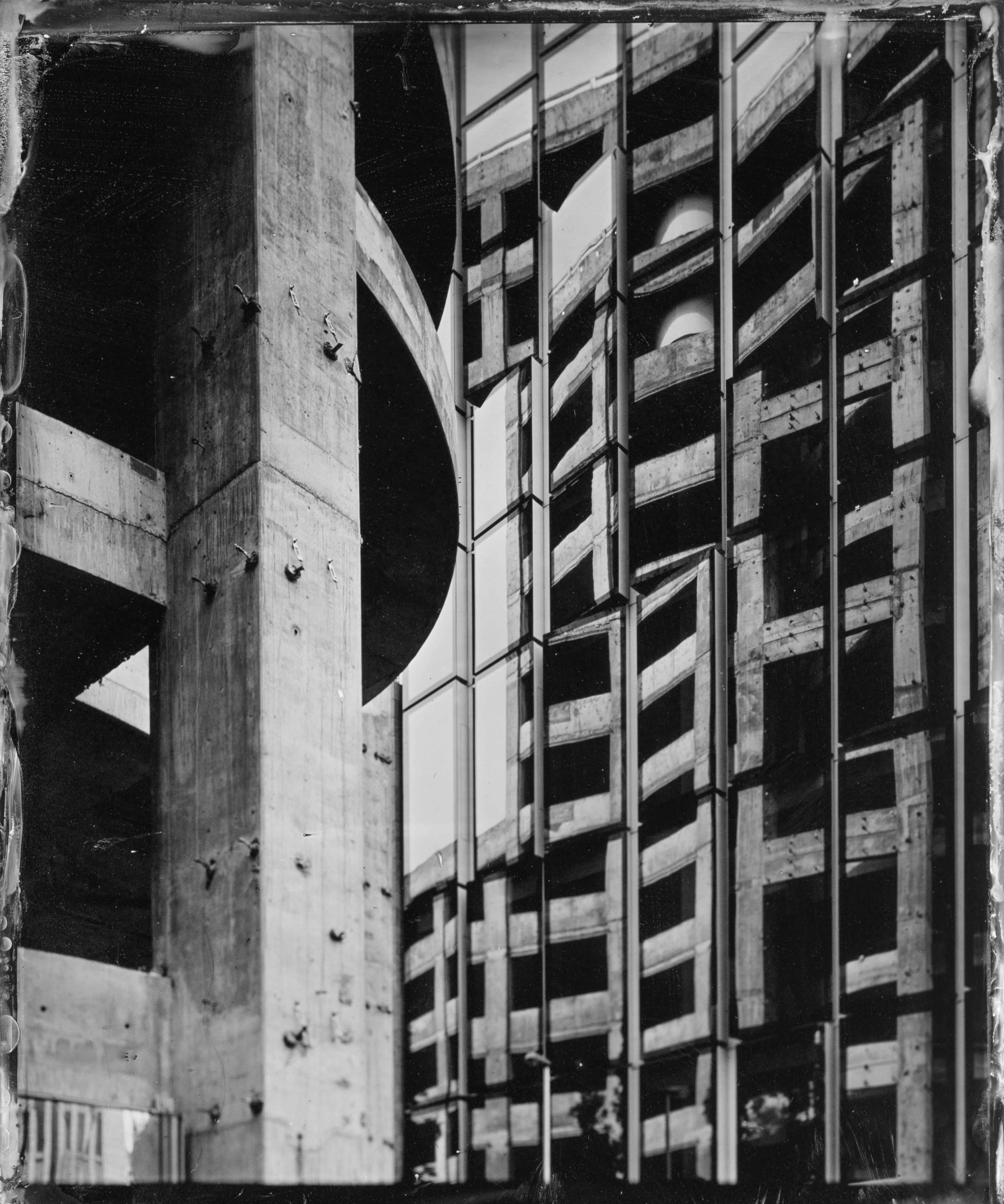

In the summer of 2020, you had a very successful exhibition with “Tin City” at the 1822 Forum in Frankfurt, and last year the pictures were on display as part of the “Lockdown Corona” exhibition at the GAF in Hanover. In a text contribution for the catalog of “Tin City,” Kristina Lemke writes: “In the age of mass-produced smartphone snapshots,Görke pays homage to single-frame photography, for whom each image is still unique.”

By this statement, is she referring to the fact that you are working with a large-format camera and the collodion wet plate technique that you used?

Wet plate collodion is an incredibly slow, complicated, and error-prone photographic process. That’s why its brief heyday from about 1850-1890 in general photography quickly ended with the advent of faster and safer processes that allowed the image medium to be carried around ready to shoot at any time and later developed at leisure in the darkroom at home, as with film.

The sensitivity of a collodion plate is about ISO 0.5-1, this already implies long exposure times, which I can only estimate. The entire recording process takes about 20 minutes. If the record is still not successful, I start again from the beginning, the next 20 minutes run. Therefore, I must have circled the perspective as well as possible beforehand, considered other perspectives and rejected them again before I finally set the large-format camera carefully, because I now think it’s worth it here. That alone can take a long time. During the set-up time and between shots, the light changes, the scenery changes. Often I break off, but every now and then something magical suddenly happens that makes the scene exciting and a picture. So as consciously as I plan the shot – in contrast to the (cell phone) snapshot – I open up a stage for chance.

Such a plate is unique because the image is created directly as a positive (in the case of aluminum plates) and cannot be reproduced. A second shot would look quite different because of the unpredictability of the chemical reactions. This is this one image, created from the reaction of silver halites and photons. In order to view the image, I don’t have to enlarge it first or convert it to a positive, project it, or clamp a print in a picture frame. I can hold the plate as is or place it on the mantel. The image on the plate thus becomes an object that does not exist again in this form. I find that tremendously exciting.

Of course, these days I can scan the plate, which goes very well because of the almost non-existent grain. The files can be used to make huge prints and transfer the image, with all its unique flaws and processing traces, into a different materiality. Here the circle to modernity closes again.

After all, the aluminum plates are light-sensitive coated immediately before the exposure and developed immediately after the exposure, how can I imagine that when you are on the road?

It is called “wet plate” for a reason. The chemical processes only work as long as the plate coating, which was infused and sensitized prior to imaging, has not dried. Only then is the layer reasonably sensitive to light and does the developer react with the silver dissolved in the layer.

Because I really wanted to take pictures in the middle of the narrow Frankfurt on wet plate, I built a mini photo lab for my cargo bike. I can get everywhere with it and carry out all the processing steps on the spot.

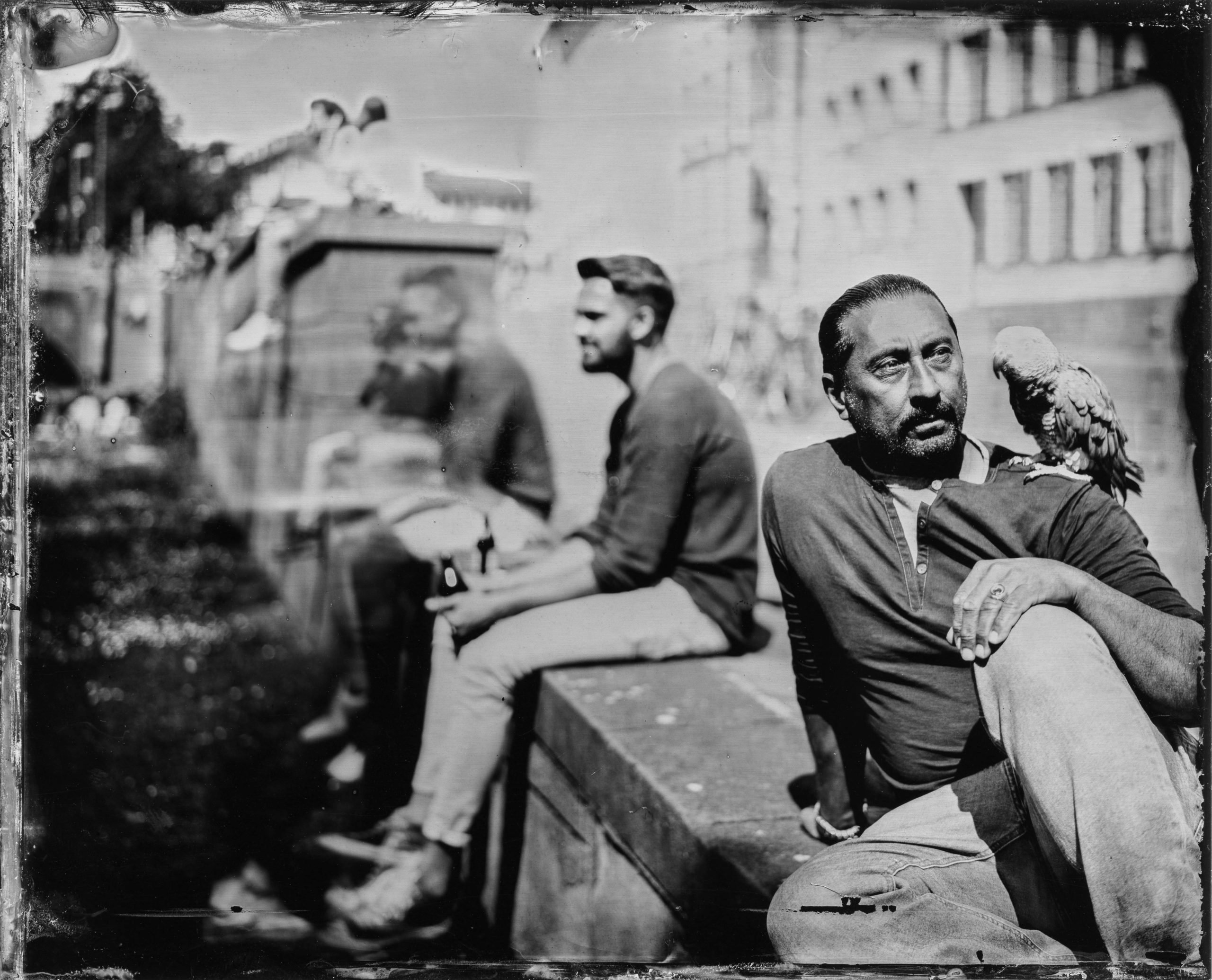

However, what is already not easy in the studio, becomes a wild thing out on the street or often doesn’t work at all. The influence of the weather on the process is much greater; I sometimes stand next to the same intersection for hours and am completely exposed. It’s dusty, the noise is distracting, and at such moments I wonder why I can’t just shoot digital or at least film.

The only thing is: the moment of taking a successful plate out of the fixer and holding this image object in your hand and looking at it is very satisfying. Then I move on or cycle back to the studio with my sweetheart.

A saying among wet plate photographers is tellingly, ” You don ‘t make a good plate, it’s given to you.”

What was the attraction for you to photograph a modern city like Frankfurt with this historical shooting process. You are only seemingly taking Frankfurt back in time, what do you want to show?

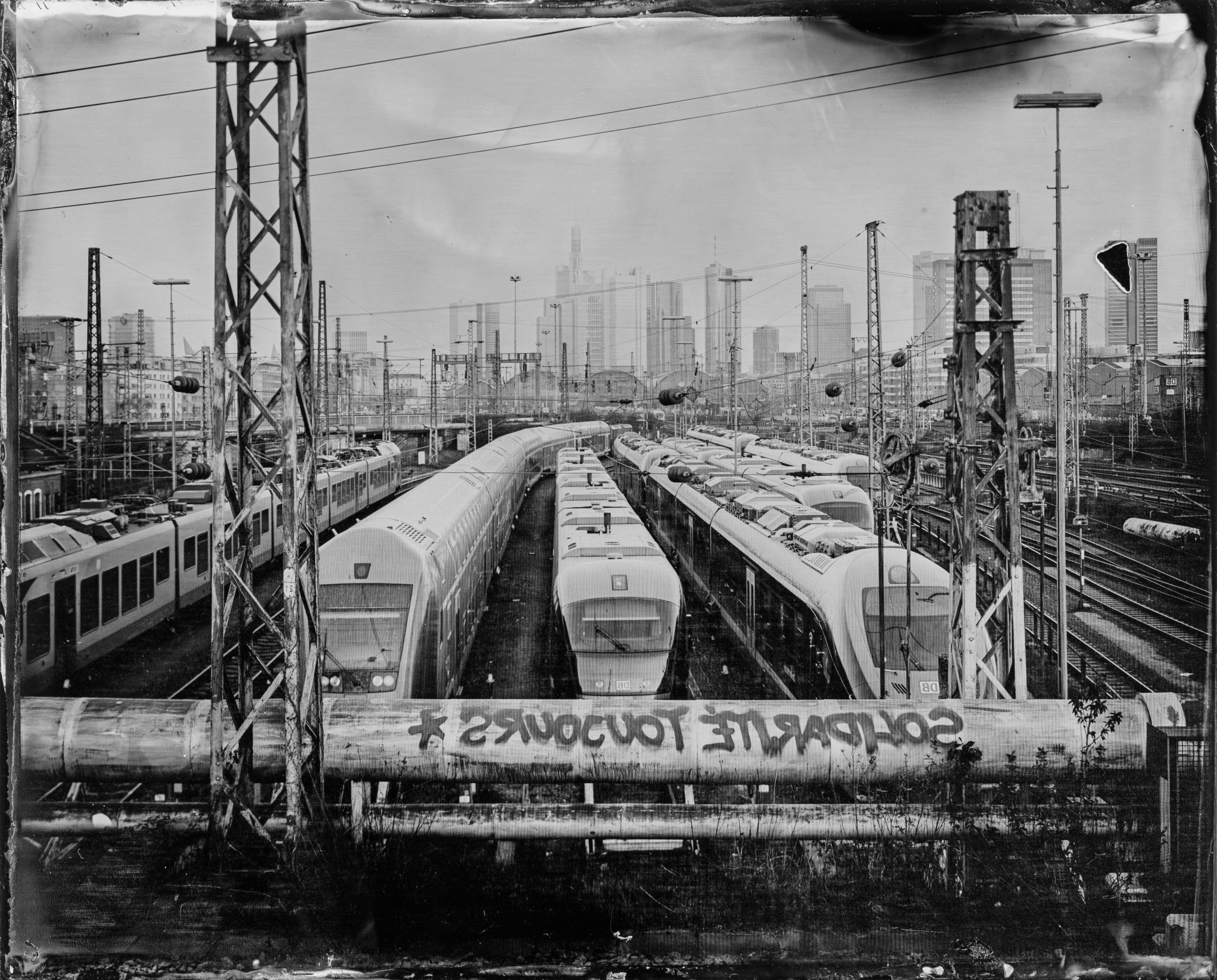

At first, I was just curious. Does it work at all to confront this big city gear with such a bulky and error-prone recording process – both technically and visually? How does today’s Frankfurt appear in photographs taken using the same process that Carl Friedrich Mylius used when he roamed the city with collodion wet plates and his laboratory hand cart in the late 19th century?

The images are mirrored (as direct positives) and the whole thing may look like Chicago in the 19th century, though the modern-familiar buildings don’t quite fit in with that. It is a conundrum with our associations and outdated habits of seeing that forces us to unravel the photographs on the plates in time and space and to mentally reassemble the city. And it thus also shows what remains of our modernity afterwards.

Beyond that, it’s simply a photographic way for me to convey, with the precision of a large format camera, but with the processing marks, the image flaws, and the dust on a plate, also the chaotic and temporary nature of the city.

Do you exclusively offer the unique prints on aluminum plates in the format 9 x 12 cm (sometimes 13 x 18cm), or are there printed editions in addition to the picture plates?

There is a print edition of most of the records in various formats. As I said, in the 21st century we have the ability to scan the plates and print them large. It’s a fascinating way to re-experience plate photographs in all their detail on a different medium. The photographers in 1860 could not.

When did you decide to switch from commercial photography to art, and why?

The desire for this intensified during the preparation of the exhibition on “TinCity“. I have never experienced photography as intensely as I did during this time, when I focused exclusively on this project and did wet plate photography on the road with all the ups and downs up and down. That’s what I want to keep doing. Translating something that captivates me into photography.

I will not be able to do without commissioned work yet. And with some customers I have a longer cooperation that continues.

What is your next project, if you don’t mind me asking? Will you remain a chronicler of the city of Frankfurt or are you drawn to other places?

Frankfurt won’t let me go in a hurry. At the moment, I have withdrawn somewhat from the city center in terms of photography, but I am very fascinated by the Frankfurt city forest in its interweaving with the outlying districts, the highways and the airport. And the Main as the zero meridian of the city I visit again and again. There I’m experimenting with a slightly larger shooting format and glass instead of aluminum plates. Again, many things go wrong and unexpected new things emerge.